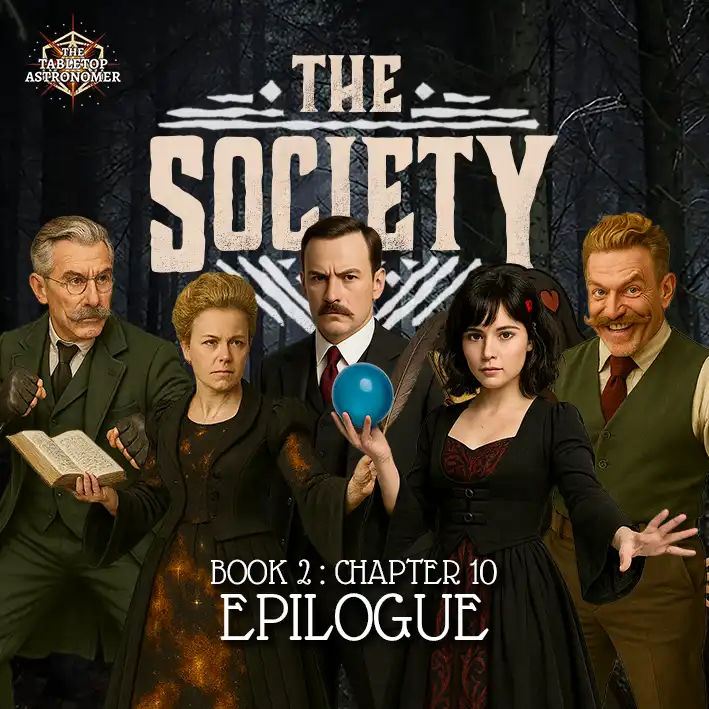

Vaesen : Of Steel and Stone : Epilogue

Sigrid

The Society came back to Granshammar bruised and hollow-eyed, but upright. The rain had broken; the air was scrubbed clean, and the sky burned with the last, low fire of sunset. A single bell tolled from the church—one final note for the director—then the village settled into its evening hush.

Sigrid made straight for the inn. Warm air met her like an embrace: coffee, fresh bread, cinnamon and sugar. Eda turned from the counter, surprise giving way to relief.

“Oh, you’re back! I’m sorry you missed the funeral, but we’re so happy to have you here. Come, sit. I’ve prepared many things—I think most of the village will be in tonight.”

“That’s excellent, thank you,” Sigrid said, already eyeing a tray under a linen cloth. “Actually, I was hoping to get some buns. I need to speak to Agnes—and I doubt she’ll come by. I don’t think she would’ve been at the funeral either, do you?”

“No, you’re quite right. I was going to send someone over with food so she wouldn’t be alone on a night like this. If you’re going, that’s perfect. Let me see what I can pack.”

Eda vanished into the kitchen. She returned with a wicker basket, still warm through the cloth. Sigrid took a grateful breath, smiled, and stepped back into the cool evening.

The path to Freedom Farm was short and kind. By the time the gate clicked behind her, one of the rolls had already gone missing. She wiped her hands, rearranged the cloth—no evidence—and knocked.

“Agnes? It’s Sigrid. May I come in?”

“Oh, yes—come in.”

The kitchen was neat, the iron stove ticking softly as Agnes fed it a few sticks and set a great coffee pot to heat. Sigrid set the basket on the table and folded back the cloth.

“I can personally attest to the cinnamon buns,” she said, faintly sheepish. “They’re up to Eda’s usual standards.”

Agnes laughed—a small, honest sound—then took a bun without ceremony. “Well, I would expect nothing less. But why did you come to see me? Just to deliver this? If so, I’m ever so grateful.”

“No,” Sigrid said, and the word gentled the room. “I thought you needed to hear the end of the story.”

Agnes stilled and nodded. “Yes… I think I would like that.”

“The short of it is that Bergs-Erik is gone. You may have noticed the weather’s improved.”

“Oh yes,” Agnes said softly. “It’s a beautiful night.”

“He won’t be back. Unfortunately, neither will your sister, Hilma. She has been keeping watch—over you, the village, your family. She missed you very much.”

There was no shock—only a long exhale, and a quiet acceptance that fit the woman Sigrid had come to know. Agnes stood, crossed to the bed, and returned with a small leather pouch.

“Under my pillow, would you believe?” She tipped the pouch, and a spill of golden beads chimed across the wood. Familiar, once dangerous; now only warm metal catching firelight. “I think this was her doing. Her last farewell. We’ll be comfortable for years—Lars and I both.”

Sigrid smiled. “Do you want to hear the whole of it, or are you content with the end? I won’t press.”

Agnes poured coffee—one cup for Sigrid, one for herself. Steam curled between them. “No. I don’t think I need to know more. The world is dark, but you and your friends have made our corner of it a little lighter. For that, I am eternally grateful.”

Sigrid reached for the cinnamon bun she had, against all odds, saved. “Then—with that over—have you any stories for me?” She opened her notebook. “I really am writing a book.”

Agnes’s eyes warmed. “Oh, that’s fun! What kind of stories are you looking for?”

She began to speak—farm years and fall storms, first snows and lost calves, the spring the river rose and didn’t stop. The stove ticked, the sky outside slid from gold to indigo, and Sigrid’s pen moved, steady as a pulse.

Sebastian

Sebastian entered Granshammar with Margareta in a fireman’s carry, boots slipping on damp cobbles, jaw set against the ache in his shoulders. The storm had broken; evening light lay thin across the square. He made straight for the inn—their base of operations.

Eda met him at the door, hands already moving. “Oh dear, what happened here?”

“We found the young lady in the woods in this state,” Sebastian said evenly. “She’s alive, but unresponsive.”

“Let’s put her to bed. There’s another room upstairs that’s free. We don’t have a doctor, so someone will need to watch her.”

“I’ll watch,” Celeste said, appearing at his side.

Sebastian carried Margareta up the narrow stairs and laid her on a clean bed. Her breathing was steady—the heavy depth of a long, untroubled sleep. He paused only long enough to see Celeste at the bedside, then turned away. There was one more duty to see to before they left the village.

He went out again to find Lars. The farm lay quiet, but the church hill was alive with motion—a stream of mourners descending, voices low. Lars walked at the edge of the group, alone.

Sebastian fell into step beside him. “Master Lars—I thought I should inform you… Mr. August succumbed to his wounds.”

Lars stopped and looked up. He said nothing at first, only nodded once, then again, holding breath against whatever wanted to break loose in his chest. “Thank you,” he managed at last. “And… I’m sorry. Sorry for not trusting you.”

“Not a problem, sir,” Sebastian said. “Honestly—I wouldn’t trust me either.”

That brought the faintest smile. “Your little group is certainly… certainly something,” Lars said. “But I am grateful.” He turned back toward the road and the people who waited for him.

Sebastian gave a curt nod and returned to the work that remained. He gathered what their frenzied flight had scattered: luggage in ditches, a bridle snagged on a fence, a horse sheltering under a willow. He checked on August’s body and made sure the wolves would find it. Practicalities, even now.

Gottfried

The rain had stopped. Sunset laid a copper edge along the eaves as the last drops ticked from the inn roof. Gottfried sat on the porch, cane across his knees, breath shallow with the day’s bruises. Villagers drifted past from the church, glancing his way with the careful curiosity reserved for strangers who have bled on one’s behalf.

“Madness,” he muttered. “Foolish, foolish professor. Foolishness…” He took a measured swig, then set the flask aside. Using the side of the building and his cane, he levered himself upright and hobbled inside. “Eda!”

“Yes?”

“Eda—please. Draw me a hot bath. The hottest possible.” His coat hung in tatters; his shirt was torn, chest and face mottled in violet and yellow. “Have someone assist me upstairs, please. Is there someone who can help me?”

Eda gave a brisk nod and vanished toward the kitchen. Sebastian, returning from the church path, caught her look and stepped in without comment. Between them, they shepherded the professor up the narrow stairs. Steam soon filled the small room; a deep tin tub waited in a clouded halo.

“Excellent,” Gottfried said, and with Sebastian’s steadying hand he eased into the heat. He let the water draw the ache from his bones until speech felt possible again. At length he rose, wrapped himself in a robe, and made his way to his room. The door clicked shut and the bolt slid home.

On the desk: jars of brine, a cloth-draped specimen among them. He lifted the cloth, stared for a long moment. “This had better work. You’ve cost me a great deal—but it is a price I gladly pay.”

He opened the jar. With careful fingers he removed its contents, patted them dry, and packed them into a small wooden box, padding the space to keep them still. The box he set aside. Then he took up pen and paper and began to write—notes to be dictated later at the castle, while the details still burned bright enough to be set in proper order.

For a while the only sound was the patient scratch of ink. Outside, the village exhaled. Inside, the professor fought the old darkness the only way he knew: by naming it, line by line, for someone else to see.

Celeste

The room above the inn was small and clean, the kind of space where quiet could gather. Celeste set two basins on the table—one warm, one cool—and worked in steady cycles: bathe the scrapes, bind the worst of them, lay a cool cloth across Margareta’s brow and change it before it could lose its chill. Outside, the village softened into evening.

For a long while the girl’s sleep was restless, her breath catching now and then as if snagged on thorns. Gradually the tension eased. Eyelids fluttered. Confusion surfaced.

Celeste moved closer. “You’re okay now. I’m looking after you. What do you remember?”

“I don’t know,” Margareta whispered. “I came into the forge… then the professor came in… there was thunder, and then—then I don’t remember. After that it was like a nightmare. I was walking in the woods, through brambles and thickets…” She lifted her bandaged hands; colour drained from her face. “It wasn’t a dream.”

“I’m afraid not,” Celeste said gently. “I don’t know if you knew Bergs‑Erik, but… he was your father.”

“What? No—no, my father lives on a farm northwest of town.”

“Not the man you’ve always known,” Celeste said. “Your biological father. He was… something different.”

“What do you mean, different?”

“What do you know about vaesen?”

“You mean—stories? Fairy tales?”

“Yes. They’re not just stories. That’s why my friends and I were in town—we were investigating strange happenings. Your master at the forge asked us to come. We got more than we bargained for.”

“Why did he ask you? What was he investigating?”

“It’s hard to explain.” Celeste drew the dagger from her belt and set it where Margareta could see. “This is intricate. Beautiful. And it holds a kind of magic—simply because you made it. You’re fairly new to the craft, yet you made this so quickly, with such detail. Your master thought something might be influencing you, or even… possessing you.

“While you are extremely gifted—I don’t doubt that—you were also being influenced by your biological father, Bergs‑Erik. He is what you’d call a vaesen. A troll. And he was using you.”

Margareta stared.

“He was trying to find a way to overcome his… let’s say, allergy to iron,” Celeste went on. “And it probably would have killed you, if we hadn’t stopped him.”

“So what happened to him then?”

“We got rid of him. He should no longer be a threat to you, or this town.”

“I suppose that’s good. I… I’m not really sure—”

“How to feel?”

“Yes. I suppose that’s what I mean.”

“Hey—we’re in the same boat.” Celeste folded the cloth and refreshed it in the cool basin. “My father is apparently a vaesen too, but I have no idea who he is. I don’t really know what I am.”

“Your father was one too?”

“My mother never talked about him.”

“Oh.”

“But here I am,” Celeste said, faintly wry.

Margareta’s gaze shifted to the dagger. “Everyone was surprised at what I could do. I was surprised, in the forge. I don’t really remember making all those details. I don’t really remember… much of it. I thought it was just focus.”

“I don’t doubt most of it was your skill,” Celeste said. “But there was a little of his influence too. When you’re feeling better, we can test a few things. I don’t know exactly what, but—this will sound strange—I can talk to the dead.

“Maybe you, in a way, can talk to metal. Maybe you can influence it, shape it how you see fit. Maybe that’s how you do what you do. When you’re stronger, we can go back to the forge. We can help each other focus. And you can see if your gift is really yours—and not Bergs‑Erik’s.”

“I… I don’t know how to understand any of this,” Margareta said, wide‑eyed.

“I know. It’s a lot.”

“And what you’re saying doesn’t actually make any sense at all.”

“No, trust me—it doesn’t. I know.”

“Then why do I feel like you’re telling the truth?”

“How could I make up something so fantastic?” Celeste managed a small smile. “I couldn’t.”

“Let me… sleep on it. We can talk again in the morning.”

“Absolutely. I’ll keep tending your wounds—if you’ll allow it.”

A moment’s hesitation, then a nod. “All right.” Margareta sank back into the pillow, and sleep returned more gently than before, while the basins cooled and the night, at last, settled.

Epilogue

Morning found the inn busy with departure. Boots thumped, trunks creaked, and the aroma of coffee threaded through a confusion of blankets, straps, and tins. Sebastian, at the centre of it, was balancing an improbable tower of pickle jars and muttering to himself.

“Why is packing up after the excursion always harder than setting off?” he said to no one in particular. “Is this our stuff or someone else’s? Why doesn’t any of it fit?”

Before anyone could answer, a soft tread sounded on the stairs. Margareta appeared, pale but upright, one hand on the rail. She looked from face to face and found Celeste.

“I wanted to say I’m grateful to you for saving me, and…” Her gaze steadied. “Let’s try.”

Celeste nodded and followed her out. At the forge, the smith took one look at them, gave a knowing tilt of the head, and left the space to the two of them. Celeste set the bellows; Margareta laid iron in the coals.

“I don’t feel any different,” Margareta said. “Not yet, anyway.”

“Just focus on your work,” Celeste answered. “What do you feel like making today? Keep your mind there and let everything else slide away. That’s how I do it.” She drew the crystal ball and held it in her palm. “Ritual first. Then I find the one I’m trying to reach, and I keep all my attention on that.”

Margareta nodded. She drew the steel, took up a hammer, and began—awkward at first, then with a steady, familiar rhythm. The forge breathed with her. It was not possession; it was craft. Calm and sure. Under her hands the metal seemed to bend to an idea more than to the blow, and before long she quenched the piece and lifted it, water beading and running from its petals: a steel rose, delicate as any in a garden.

“I… suppose at least part of it was me, then,” she murmured, almost surprised by her own hands.

“All of it was you,” Celeste said.

Silence pooled, warm with the forge heat, until Margareta looked at the floor. “So… what are you going to do now?”

“Keep working with my friends,” Celeste said. “Help where we can. You could come with us. There’s room. You could learn more about yourself—help us prepare, and be prepared.”

“I don’t know about my father. My… my real father.”

“Think about it,” Celeste said gently. “The man who raised you is your father. That matters most.”

“Maybe,” Margareta said. “He’s here and… maybe he needs me. I don’t know.”

“Think on it,” Celeste repeated.

They let the forge go to embers and walked back in companionable quiet. Something in Celeste’s calm had found its mark.

By late morning the Society had loaded most of what they meant to keep. Sebastian was still fitting the last jars into a crate when he spotted Margareta striding across the square, a small satchel over her shoulder. She stopped before them, suddenly nervous, then pushed through it.

“I… I would like to come with you, if you will have me.”

Celeste pulled her into a hug. Margareta returned it, then faced the others. “I don’t know what all of this will be, but if I can help, I want to. I might not fight vaesen as you do, but you’ve seen what I can make. I can craft things to keep you safe—if you’ll let me.”

Sigrid’s first look was full of concern—about uprooting a girl with nothing but a satchel and a gift.

“No,” Margareta said, catching it. “I spoke to my father yesterday. He thinks—and I think—it would be good for me to leave for a time. After everything with August…” She shuddered, then steadied. “His friend will write me a recommendation to a blacksmith in Uppsala. An old acquaintance. I’ll have work. I just want to help.”

“I think you’ll do just fine,” Celeste said, linking arms with her.

Sigrid smiled and offered a hand up to the cart. Gottfried, watching, looked very sad but said nothing. At last he tugged on Sebastian’s sleeve. “Sebastian, this reminds me—there’s a package for me somewhere around here. Perhaps at the other inn, or en route. Could you speak with Sven? He might know which way it went. I’d like that before we leave.”

Margareta, hearing, touched Gottfried’s shoulder. “I’m so sorry, sir.” She lifted her satchel. “I think we have everything.”

Unless any soul had more to say, the road waited—the Society, now with one more in their number.

Epilogue: The Message

Morning at the castle felt thinner, as if a single room on a far corridor had been emptied in the night and the draft had found every door. Mr. Frisk approached the Society carrying a sealed leather tube and a small oak case. In the hall he set a phonograph on a table, fitted a wax cylinder, and wound the key. The machine crackled to life.

“Dear Society,

By the time Mr Frisk hands you this wax cylinder, I will be halfway home to Hinterwald Manor in Germany.

I have made many mistakes in our brief time together—costly mistakes born of overconfidence in my meagre abilities. The result is a painful lesson: what works against vaesen in the Black Forest does not necessarily work elsewhere. I have been fooled time and again, and my precious books have failed to be of use most of the time. I thought myself a wise genius—but that is exactly what a fool might believe. I have been like children playing on the beach while a tidal wave bears down in the distance—oblivious. We only survived by the skin of our teeth, and nothing I did changed that.

SEBASTIAN

We have known each other for over a decade. Over the years, you have become more than a mere employee. You have been a good friend—perhaps my only friend. You know me better than I know myself. And still, in my narcissistic arrogance, I have been selfishly cruel to you. You are ten times the man I will ever be, and so I thought to pass the legacy of the Höllenjägers to you—to hone you, to toughen you enough to be the heir of Hinterwald Manor and its next steward. This is another failure on my part. I tried to escape my burden by foisting it upon you. I hope that you will one day forgive me this selfishness. In that light, you are free now to make your own path. No more cleaning up after my messes—now you may make your own. Your regular stipend will continue, so money need not stand in your way. Go and find your destiny, my friend.SIGRID

We have not seen eye to eye on many things—mostly for good reason on your part. The darkness of past traumas taints my every decision and clouds my judgement. I thought you oblivious to dangers lurking around every corner—shouting out our plans within earshot of enemies who could end our lives in an instant. But that was not it at all. It was fearlessness. You are less afraid than I am. For years I have used only righteous anger to give me strength against fear. You use something else—hope, perhaps? Whatever it is, it makes you stronger than I will ever be, and I envy that gift.

When you gave the bear your hand, it was not your mistake but mine that cost you your finger. I was so certain it was Hilma. But sometimes a bear is just a bear. I cannot undo what is done, not entirely. But I have done what I can. Please accept this gift in the spirit it is meant: to make amends for my foolishness. Mr Frisk—please give her the box now.CELESTE

I think we worked well together—particularly around the unfortunate murder of the director, a matter for which I believe I share responsibility. I taunted him, that fool August, thinking he would run or blunder. Instead he did what any cornered animal does: he fought tooth and nail.

I sense a kindred spirit in you, Celeste. Unfortunately, that is not a good thing. I do not know what you are, other than someone with astounding potential. But, like me, you are touched by the dark—guided by it, drawn to it, and it to you. I hope you can control this before it controls you. Before it ends you. We need more light in this world to keep even the shadows at bay—let alone the dark.Goodbye, and good luck to you all.

—Gottfried.”

The needle lifted with a soft click. Silence gathered in its wake.

Sigrid surged to her feet halfway through the section bearing her name. By the end she was pacing, furious. “How dare he? How dare he think his trauma is so much greater? Oh, if I ever get my hands on him—” Her glove lay forgotten on the chair.

Sebastian’s face did not change at first. He stood very still, the set of his shoulders as familiar as the furniture around him. Then, minute by minute, the posture loosened. He sat, elbows on knees, head in his hands, listening to the quiet tick of the hallway clock.

Celeste’s expression held anger like Sigrid’s—and sorrow under it. The sorrow won. She left without a word, down the corridor to the range. There, with Margareta’s dagger, she threw—hard, harder—accuracy be damned. Motion, breath, impact; again and again until the air steadied.

When Sebastian finally rose, Sigrid stepped close and set a hand on his shoulder. “He could leave you just like that, huh? After all those years?”

“A decade of work… just…” Sebastian straightened. “If you’ll excuse me, I have to write a letter.” He nodded and turned away—nothing like his usual posture, the weight obvious.

As he moved past, Sigrid caught his sleeve. “Sebastian… you’ll stay with us, won’t you? Even without him?”

“Of course, madam.”

“Good,” she said, and kissed his cheek before heading upstairs.

So the Society stood a while, each with their own grief: anger, loss, betrayal—the empty space at the table speaking as loudly as any voice. Outside, Uppsala’s morning went on, indifferent and bright.

Epilogue: Dinner & Guests

By evening the castle felt lived‑in again. Mr. Frisk had been busy: carpets beaten, brass brightened, a roast sending its comfort through the corridors. The Society gathered in the dining room beneath a chandelier that caught the last of the day.

Margareta joined them, soot at her cuffs, hair pinned up. She had spent the day measuring an outbuilding and declared it perfect for a forge; she and Mr. Frisk had already begun discussing coal deliveries and chimney draws. Frisk, for his part, set the platters down and—quite against habit—insisted Sebastian take a seat and be served rather than hover.

Sebastian obeyed. He looked dishevelled: no blazer, tie loosened, the top button undone. One of Gottfried’s bottles had found its way into his hand—there seemed an endless stock of them—and there was a slight sway to him as he crossed the room.

Sigrid had mail. She waited until plates were filled and cups poured before she stood, beaming, a thin letter in hand. “I have such exciting news! Two of my stories—the one about the small child and the fairy, and the other I told you about, Celeste—are being published.”

“Do you have a copy?” Celeste asked.

“Not yet, but it’s coming out in a couple of weeks.” Sigrid held up a cheque. “They even sent this. Not a fortune, but decidedly better than a local column.” her cheeks flushed. The letter added more: They had claimed first look at whatever she wrote next. Not aspiring now. Author.

The bell rang—loud, insistent. From the kitchen came the clatter of dropped pans as Mr. Frisk attempted to sprint with dignity.

“I’ve got it, don’t worry!” Celeste called, slipping from her chair. She crossed the entry hall and opened the front door to an elderly woman on the stoop, wrapped tight against the night.

“Aye, you there—the high muckety‑muck that owns this place?” the woman demanded.

“…The what?” Celeste blinked.

“Are you the owner?”

“Sort of. Me and some others.”

“I’m Grable, Missus Grable. I’d like to talk to the rest of your owners, if you don’t mind.”

“Come on in.” Celeste led her to the dining room. The woman sniffed. “Look at this place—you’re living in the lap of luxury, huh?”

“Definitely nicer than my last place,” Celeste said.

“And who are you, then?”

“I’m Celeste.”

“Celeste—the last yell. That means heaven.” Grable squinted past her. “Who’s the rest of your gang?”

“That’s Sebastian—he’s a little under the weather. This is Sigrid—she’s just getting published. And this is Margareta.”

“Ain’t she a waif?”

Celeste’s tone turned mildly protective. “I wouldn’t mess with her—she makes our weapons.”

“Weapons? What you need weapons for?”

“What do you need to know that for?”

Grable harrumphed. “Right, right—I forgot why I was here. Tell me, does the name Annabelle Linton mean anything to any of you?” Her gaze settled on Sebastian.

Sebastian stared. “…Was that Annabelle…?”

“Linton.”

His flask slipped from his fingers and struck the carpeted floor with a muffled clatter.

“I thought it might mean something to you… Mr. Sebastian G. Dornez—if that’s your real name,” the old woman said sweetly.

Sebastian’s pupils sharpened; sobriety seemed to return all at once. Then the woman reached up and tugged. The face peeled away with a disquieting elasticity. Beneath stood a man in his forties, composed, watchful.

“Reginald Smythe,” he said with a small bow. “At your service. Military Intelligence.”

Sebastian rose. “Well, Dornez,” Smythe continued, eyes never leaving him, “it’s been some time. I’ve looked forward to meeting you.”

“…Yes. I…” Sebastian began.

“Hello?” Celeste said carefully, looking between them. “What is going on? I mean—I talk to dead people, but someone pulling their face off? That’s unusual even for me.”

The bell rang again. Mr. Frisk entered with a sealed envelope on a tray. “Sir, there was a letter for you.” The wax was black, stamped with the device of a dog—unknown to all but one.

Sebastian took it without a word, eyes briefly flicking to Smythe. “This was not the day to bring my sobriety…”

Sigrid poured him coffee. He drank it in one swallow, still steaming, and stood. “Madams, sir—thank you for making the trip, but I must deal with this.” He left the dining room and turned toward the small library, the envelope unbroken in his hand.

Behind him, conversation held its breath. The door clicked shut.

Beyond the oak panels, the wax seal waited under the lamplight, the dog’s head stamped in midnight. The castle seemed to lean closer, listening for the first tear of paper.

Sigrid let Sebastian go, then turned back to the visitor. “Mr. Smythe, would you like to join us for a cup?”

“I would. I am famished.” He took a seat without waiting to be asked twice, unfolded a napkin, and tucked it at his neck with precise, almost surgical neatness.

Celeste laughed. “For a second I thought you were about to tuck the tablecloth in there.”

“And why not?” Smythe replied, and set about the roast with unembarrassed gusto.

There was plenty to spare; most at the table had little appetite. Celeste ate as usual—anger at Gottfried simmering under a genuine lift in her mood: Margareta was here, one more person who felt like her; Sigrid had good news. Concern for Sebastian tugged, but she gave him space.

Smythe chewed, silent, his gaze unfocused in the particular way of a man replaying what he had just seen. He filed away the angle of Sebastian’s shoulders, the way the flask had slipped, the flicker at the sight of the black‑wax seal. He did not press; he catalogued.

To give Sebastian time, Sigrid poured tea and offered idle conversation. “Lovely day we’re having, isn’t it? Did you come far?”

“Yes, yes, quite. Not too far,” Smythe said, eyes still tracking the geography of the platter.

At length he looked up. “I’ve been studying your little group for some time. It’s… interesting to meet you all in the flesh, as it were.”

“Studying us?” Sigrid asked.

“Yeah—why?” Celeste added.

“Well,” Smythe said, dabbing his mouth, “I’m here on a mission for the Bureau. I’m looking to recruit your little group for something special.”

“And how would the Bureau even know of an obscure group of travellers—just sightseeing about?” Sigrid’s tone was light; her eyes were not.

“You’d be surprised at the things we hear.”

“Did you say what Bureau you belong to?” Celeste asked. “Or is it just the Bureau—like we’re the Society?”

“I said military intelligence—earlier.”

Which, even to Celeste’s ear, was so vague as to be useless.

“So—military intelligence of what military?” Sigrid pressed.

“I thought my accent might have given it away,” Smythe said dryly. “British military intelligence.”

“Right…” Celeste murmured.

“They had some?—excuse me,” Sigrid said, a small smile touching her mouth.

For the first time, Smythe’s right eyebrow climbed a fraction. His expression did not soften. It seemed carved into a permanent scowl—not anger, just architecture.

“So this Bureau you mentioned—is it part of military intelligence as well?” Sigrid went on.

“It is,” Smythe replied. “I’m essentially an attaché to the Swedish government. Military projects, and all that.”

“We have nothing whatsoever to do with the military,” Sigrid said evenly, “and I believe I speak for everyone when I say we’d like to keep it that way.”

Celeste nodded and kept eating.

“Indeed,” Smythe said. “However… Mr. Sebastian is a subject of Her Majesty.”

Queen Victoria’s shadow seemed to touch the table.

“Perhaps he would like to do something for Queen and country.”

“That would be entirely his decision,” Sigrid said. “I suppose.”

“Of course,” Smythe allowed. “And given the nature of that—”

“It still doesn’t explain why you’ve been… studying us.” Sigrid had risen without seeming to; she stood very straight, looking down the length of her nose at him.

“…Assassinating groups, are we?” Smythe’s mouth barely moved.

Before Sigrid could answer, Mr. Frisk slipped in and leaned to murmur in Celeste’s ear; she frowned, whispered back, “Secrets all over the place,” and Frisk withdrew.

Smythe went on as if reading from a report. “I’ve been receiving notices of your… unusual activities. An informant mentioned a crew of half‑mad sailors, raving that their captain had sold his soul to Satan. This on a vessel bound for Svalbard. Their troubles began after taking aboard a strange shipment in Sweden—from a German professor, accompanied by a well‑dressed gentleman who, curiously, is no longer in this room.

“I have also read articles about a place called Stegeborg. Eyewitnesses placed your Society squarely in the thick of things.”

Celeste rubbed at her leg, stood, and left the room without a word.

“Oh yes,” Sigrid said, still watching Smythe. “I remember that story. I even published it. A cascade of lies, of course—but it was the story that went out.”

“I read the draft this morning,” Smythe said. “Very good work.”

“I fail to see what about that would interest the military—or England in general.”

“Well,” Smythe said, “people going mad and seeing spirits seems to occur wherever your Society goes.”

“We’ve been exactly one place where that happened,” Sigrid said. “Forgive my confusion.”

“One place together,” Smythe corrected.

“And it happens nowhere else? With other groups of people?”

“Not with these odds.”

Celeste left the dining room, crossed the entry hall and the salon, and paused at the small library’s door. It was closed. She opened it to find Sebastian within, the lamplight turned low, the black‑sealed letter in his hand.

“Are you all right? Are we fighting this guy? What are we doing?”

“Not immediately, Miss Celeste—though he is one to keep an eye on.” He weighed the opened envelope once, then lowered it. “I… I am not in the right state of mind for all of this. It’s becoming too much. I need to confide in someone. Tell me—”

Celeste sat beside him without a word.

“Is our guest currently being occupied by Miss Sigrid?”

“Absolutely.” Celeste cracked the door, took a quick look down the corridor. Sigrid and Smythe were practically nose to nose, mid‑argument. She closed it again. “Very.”

“Yes…” He drew a breath. “Between Master Gottfried’s message, Bergs‑Erik, Smythe turning up—and now him calling out the name of my deceased wife… This is—” The words failed for a moment. He took a long swallow from a flask, then straightened and, with a brittle formality, gave a small salute. “Captain Charles Wyndham. Former Third Royal Scots Regiment. Agent of Department M—Her Majesty’s secret bloody service.”

“That’s a lot to take in,” Celeste said softly. “So… are you undercover right now?”

“Yes. I have been for the past ten years. Operation Foglight: observe and report on a grieving lunatic meddling in old magic.”

“Gottfried.”

“Exactly.”

“So what were you supposed to do with Gottfried? Just watch him?”

“Essentially. Watch him—and report back to London if he came undone. His family has a history with the occult, old magic, and monster‑hunting. That worried someone in a suit. I was told to befriend him.” He let out a breath that might have been a laugh. “He called me his only friend—you heard the message. His only friend. And I’ve been lying to him since the day we met.”

Betrayer, hissed a voice that wasn’t in the room. He flinched as if from a draft.

Celeste set a hand on his shoulder. “I can understand why you’re drinking a little. Sit. Do you want a tincture—something to clear the fog out of your head?”

“I would appreciate that. I don’t know how he stands this stuff.” He tossed the flask, and it thudded against a bookcase. The smell it left was brutally strong, with a waxy tang—something like lard.

Celeste opened her satchel, set a kettle on the small spirit burner, and worked by habit and scent—peppermint to lift, willow bark for the ache, a pinch of rosemary to sharpen the edge. She poured when the water sighed and handed him the cup.

“So—your real name is Charles… what?”

“Charles Wyndham.”

“It may take me a while to get used to that,” she admitted, managing a small smile. “I’m sorry about your wife.”

“Thank you,” he said, steadying around the heat of the cup. “That is a story for another time. For now… let’s see what Mr. Smythe wants, and play along for the moment.”

The lamplight hummed. Beyond the door, voices rose and fell; somewhere down the corridor a clock struck the hour. Sebastian looked once more at the black wax and the dog’s device impressed there, then set the letter on the table between them—an answer deferred, but not for long.

Back in the dining room, Mr. Smythe found more resistance than perhaps he expected.

“Don’t you think you’re jumping to conclusions, sir,” Sigrid said, voice cool, “assuming we had anything to do with these events?”

“Yes—all of the witnesses must be completely wrong, then,” Smythe replied.

“We recorded it,” Celeste said mildly.

“You can’t trust witnesses.”

“We were there,” Celeste returned.

“We were certainly there,” Sigrid allowed.

“Indeed,” Smythe said. “And yet these witnesses—untrustworthy though they may be—claim you started a riot. That a girl’s father died. Yes, you rescued her. But apparently she was stabbed. I’ve read it all in the reports.”

“Absurd, sir. Villagers invent such tales,” Sigrid said.

“Well, I’m sure some of these would be punishable as crimes in Sweden. Fortunately, I am not a constable.”

“Punishable crimes?” Sigrid’s chin lifted. “I’m not aware of any being committed. Exactly what do you mean?”

“Laudanum smuggling, for one. The riots—the murderous riots.”

“We had no part in laudanum smuggling—that was the reverend.”

“Then it is quite good you are not in front of a magistrate,” Smythe said.

Sigrid held his stare. He watched the minute shift of colour in her cheeks and knew her bluff for what it was. At the same time, Celeste’s shadow slipped closer at his shoulder. Smythe’s gaze flicked once; the wallet stayed where it was.

“I can have more made, if you’d like, my dear,” he murmured to the room at large.

Celeste’s eyes narrowed. “What is your purpose here?”

“As I said—recruiting your Society. I have a mission.”

“She wasn’t in the room when you said that,” Sigrid noted.

“That’s right,” he said.

“So you came to us dressed as an old lady,” Celeste said. “Why the subterfuge?”

“Dramatics.”

“Why?”

“I like to make a splash when I introduce myself.”

“Play‑acting,” Sigrid said.

“If you’re trying to win our favour,” Celeste added, “that isn’t the way to do it.”

“Well then—how about this?” Smythe gestured to the ceiling. “Your castle could use a few upgrades. I have the power of the state behind me. I can make that happen.”

“And you know for a fact our castle needs upgrades?” Celeste asked.

“From my research, yes. And, frankly—it doesn’t take more than half a glance.”

As if on cue, a flake of plaster surrendered from the ceiling and fell with a soft plop into the bowl of mashed potatoes.

“There you go,” Smythe said. “Proof enough.”

Sebastian returned then—jacket on, tie straightened, a bracing brightness in his step. “I had a couple of extra packets of wake‑up powder,” he said to Sigrid’s arched look.

“Well, Charles,” Smythe said, then corrected himself with a thin smile, “—I’m sorry. I meant Sebastian.”

Sigrid shot Sebastian a startled glance.

“I’ll explain later, madam,” he murmured. Then, to Smythe: “Mr. Smythe—sir—how may we be of assistance to you?”

“Yes, you will,” Celeste said under her breath, hands clasped behind her back to conceal the dagger she habitually wore.

“I am the director of the Bureau,” Smythe said evenly. “A division of the Topographical and Statistic Department—T&SD. The new information hub of Her Majesty’s government. And I could use your help on a certain matter… involving curious things.”

“We are but a humble selection of unimpressive individuals,” Sebastian said smoothly. “How may we be of service?”

“Unimpressive?” Smythe gave a short, genuine laugh. “I would be surprised to meet anyone more impressive than your group.”

With Sebastian back, Sigrid let her stance soften and took the edge of a chair, very straight‑backed. Celeste remained standing, composed, ready.

“I have been trying to find out more about this shipment to Svalbard,” Smythe continued, “and what happened to those men. But I’ve received rejection after rejection from the top brass—which should be impossible, since I am the top brass. Each rejection is signed only with ‘Dept. M.’ I do not know if that means Deputy Minister, or something else.

“What I do know is that Mr. Dornez is connected to this matter.”

“How so?” Celeste asked. “What evidence says he is?”

Smythe’s gaze fixed on Sebastian. The pause lengthened. The meaning was clear: this could be public, or private.

Sebastian steadied. “…No. Carry on.”

“Very well,” Smythe said. “I’ve been given carte blanche—the authority to investigate and deal with this situation. And it concerns one Annabelle Linton.” He let the name settle. “Someone you may know better, Mr. Wyndham… as Jade Cheshire. Your wife.”

“Mr. who?” Sigrid asked, the room tilting a fraction.

Sebastian exhaled. “…Yes, madam. Sir. I suppose there is no hiding it now. I had hoped for a better moment—but yes. I have lived under an assumed name for the better part of ten years. My real name is Charles Wyndham.”

“…Does the professor know?” Sigrid asked.

“He is unaware,” Sebastian said. “As far as I know.”

“I see.”

Celeste did not look surprised.

“And the last time you saw Miss Cheshire,” Smythe asked gently, “how would you say she was feeling?”

“To be blunt,” Sebastian said, “the last time I saw my wife, she was dead. Moments before that, we were in matrimonial bliss in the Highlands of Scotland.”

“Please, sir,” Smythe said, glancing at the plates. “We are seated at dinner. Let us have composure. Regardless… Miss Cheshire—your wife—did not die.”

Sebastian reeled, colour draining, as if the room had been tilted and all the air rushed to one side.

Smythe did not blink beneath the weight of the room’s silence. “Yes indeed,” he said at last. “She was an actress when I met her. Jade Cheshire was her stage name. She had a gift for coaxing people into spilling their secrets. I recruited her.”

He ate without hurry as he spoke, the facts arranged like cutlery. “As an agent, your wife assisted me in dismantling a Russian information ring with ties to a local raja in India. After that, she returned to Britain to escape retaliation. A few years later, when I came back to London, I discovered she was working undercover for the Royal Navy. Two missions: recruiting promising new operatives and counter‑espionage.” His mouth curved, almost a smile. “That’s when she went AWOL—in your care. I’m not sure how her mission tied to you, unless she had simply gone absent without leave… a phrase I’ve just coined. Because it is 1859. And I am ahead of the game.”

“Undeniably,” someone murmured.

“I have investigated her supposed death,” Smythe continued, “and every time I am stymied by a mysterious department I should know about—but do not. Hence, I would like to retain your services. The services of your group.”

Sebastian stood very still, the quiet around him growing weight.

“You are the only registered witness to her so‑called death,” Smythe said. “Actually… there is one other witness. But I do not know who it is. No matter how much I press, I cannot find out.” He leaned forward. “But I did discover one more thing, Mr. Wyndham. Apparently, your wife had a son. During the years she was missing, she used the name Sarah Breckenridge.”

“…A child?” Sebastian’s voice was thin with disbelief.

“I would presume so, yes. Most of the time when children are born… they are children.”

Sigrid let out a breath she had been holding. “Sounds like she’s had even more names than you, Sebastian.”

“Jade Cheshire,” Celeste repeated, as if tasting the shape of the words. “And Sarah Breckenridge.”

Smythe’s gaze skimmed the table. “I have noticed your professor friend is not here. Where might he be? I would like to question him.” He waited a beat. “Don’t all speak at once.”

“He is out of town,” Sigrid said. “Called away unexpectedly.”

“How convenient.”

“Not really,” Celeste said. “And we don’t know when—or if—he’ll return.”

“I shall ask my agents,” Smythe said. “I am sure they will have much to tell me.”

“It remains distasteful,” Sigrid said, the words clean and precise, “that you—and the English government—are investigating people who are in no way under your power or jurisdiction.”

“As I said, I am an attaché to the Swedish government,” Smythe replied. “I operate with their authority, on their soil. Liaison.”

Sebastian shifted, uncomfortable at the geography of the argument.

“I have heard nothing to suggest the Swedish government has any interest in us at all,” Sigrid said.

“They are very interested. I have—fortunately for you—kept that interest in check.”

“What is it about us they are so interested in?” Celeste asked.

“You were out of the room,” Smythe said. “Riots. Murders. Laudanum smuggling.”

“He has a whole folio from Stegeborg,” Sigrid said dryly.

“Okay,” Celeste said, “we did not start a riot. What else did you say?”

“Laudanum smuggling,” Sigrid echoed.

At that moment an empty Gottfried bottle rolled obligingly across the floorboards, glass whispering on wood.

“…Yes,” Celeste said, pinching the bridge of her nose.

“And murder,” Sigrid added.

“The father in the bed,” Smythe clarified. “And the girl was stabbed by the professor—in order to save her. Which is assault, not murder.”

“You have a folio of accusations without merit,” Sigrid said. “Wild tales. Why the villagers would invent such things, I cannot imagine.”

Celeste’s fingers tightened at her sides. Power prickled along her skin, a familiar urge to show him what he was dealing with—just a taste. Sigrid’s hand found hers, grounded it.

“Celeste,” she said quietly, “don’t you think this is all just stories? Can you think of any reason he’s making these tales? Chill. It’s absurd.”

Celeste exhaled, eyes hot across the table. “I don’t know where he’s getting his information,” she muttered. The look she sent Sigrid said the rest: he is really annoying me.

“Perhaps we will simply turn those matters over to the authorities,” Smythe said mildly, “and let them decide. In the meantime, my request stands. I would like your assistance—and you will be paid for your services.”

“Specifically what services?” Celeste asked. “We need details.”

“To do what you do best,” Smythe said. “Investigate a curious matter.”

“We are history buffs,” Celeste said blandly. “We roam around, look at things, learn the history.”

“You know how it goes,” Sebastian added, straight‑faced. “Exploring spooky old buildings, only to find it is just a man running around—”

“—in a rubber mask,” Celeste supplied.

“Rubber,” Smythe repeated, amused. “An unusual turn of phrase.”

“Above the table,” Celeste said briskly, “if you are offering to pay for upgrades and pay us for this, we should ask for things. Can you get us armour?”

“There is an armour table,” Mr. Frisk observed from the doorway, as if this were an entirely ordinary part of dinner.

“I know a smith who could forge armour for you,” Smythe said. “I would be willing to cover that—with state finances.”

“I could probably—” Margareta began, then stopped herself and slipped quietly into the kitchen.

“You understand,” Sigrid said softly.

Celeste nodded. Then, to Smythe: “It is a surprise to most of us. If you will excuse us, we would like to discuss this—and perhaps we can get back to you in a day or so.”

“Of course. Quite reasonable.” Smythe took one last chicken leg, finished it neatly, wiped his mouth, and stood. “I look forward to hearing from you—one way or the other.”

Sigrid tilted her head in a brisk nod. “Mr. Frisk?”

There was a bell‑pull; she tugged it. Frisk appeared at once. “Yes, madam?”

“Mr. Smythe will be leaving now.”

“Quite, madam. Though—there is something you may all wish to see.” He led them across the hall and out into the courtyard.

The sky above Uppsala was alive. The northern lights bent and whirled in a vast spiral, brighter than any of them had seen, converging over the city as if it were the eye of a storm.

“I thought perhaps you ought to know,” Frisk said. “Sir. Madam. Mr. Smythe—your hat.” He offered the old lady’s bonnet on a gloved palm.

“And your face, sir,” Sebastian added dryly.

Smythe tucked the hat away and glanced sidelong at Sigrid. “Well, well. Another coincidence.” He about‑faced and walked off. A minute later, they glimpsed him step into the trees and vanish—only for a little old lady to step out the other side.

As the group turned back toward the door, Sigrid linked her arm firmly through Sebastian’s. “Shall we go in and discuss this?”

“Yes, madam.”

Celeste took his other arm. “I could try to see if she really is dead, you know.”

“That is an interesting thought,” Sigrid said.

“She is…” Sebastian began, then closed his eyes. “I prefer to think she is. But yes—I believe I have some explaining to do.”

“Just a little,” Sigrid said.

The castle breathed once in the cold, green light, and the night seemed to tilt toward whatever came next.